En voor wie er nog niet genoeg van heeft, Jeff Halper, van het ICAHD, (Israeli Comittee Against House Demolitions), expert in de feiten van de kolonisatiepolitiek van Israel, vat de situatie nog eens uitgebreid samen. Het haalt heel wat van de recente mythes omver, onder andere dat het de Palestijnen zouden zijn die geen vrede willen of geen eigen Palestijnse staat. Het verdient vertaling, helaas heb ik daar op dit moment geen tijd voor.

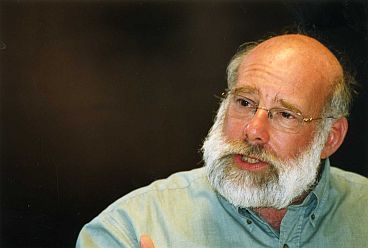

Jeff Halper

November 23, 2006

Let’s be honest (for once): The problem in the Middle East is not the Palestinian people, not Hamas, not the Arabs, not Hezbollah or the Iranians or the entire Muslim world. It’s us, the Israelis. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the single greatest cause of instability, extremism and violence in our region, is perhaps the simplest conflict in the world to resolve. For almost 20 years, since the PLO’s recognition of Israel within the 1949 Armistice Lines (the “Green Line” separating Israel from the West Bank and Gaza), every Palestinian leader, backed by large majorities of the Palestinian population, has presented Israel with a most generous offer: A Jewish state on 78% of Israel/Palestine in return for a Palestinian state on just 22% – the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. In fact, this is a proposition supported by a large majority of both the Palestinian and Israeli peoples. As reported in Ha’aretz (January 18, 2005):

Some 63 percent of the Palestinians support the proposal that after the establishment of the state of Palestine and a solution to all the outstanding issues – including the refugees and Jerusalem – a declaration will be issued recognizing the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people and the Palestinian state as the state of the Palestinian people…On the Israeli side, 70 percent supported the proposal for mutual recognition.

And if Taba and the Geneva Initiative are indicators, the Palestinians are even willing to “swap” some of the richest and most strategic land around Jerusalem and up through Modi’in for barren tracts of the Negev.

And what about the refugees, supposedly the hardest issue of all to tackle? It’s true that the Palestinians want their right of return acknowledged. After all, it is their right under international law. They also want Israel to acknowledge its role in driving the refugees from the country in order that a healing process may begin (I don’t have to remind anyone how important it is for us Jews that our suffering be acknowledged). But they have said repeatedly that when it comes to addressing the actual issue, a package of resettlement in Israel and the Palestinian state, plus compensation for those wishing to remain in the Arab countries, plus the possibility of resettlement in Canada, Australia and other countries would create solutions acceptable to all parties. Khalil Shkaki, a Palestinian sociologist who conducted an extensive survey among the refugees, estimates that only about 10%, mainly the aged, would choose to settle in Israel, a number (about 400,000) Israel could easily digest.

With an end to the Occupation and a win-win political arrangement that would satisfy the fundamental needs of both peoples, the Palestinians could make what would be perhaps the most significant contribution of all to peace and stability in the Middle East. Weak as they are, the Palestinians possess one source of tremendous power, one critical trump card: They are the gatekeepers to the Middle East. For the Palestinian conflict is emblematic in the Muslim world. It encapsulates the “clash of civilizations” from the Muslim point of view. Once the Palestinians signal the wider Arab and Muslim worlds that a political accommodation has been achieved that is acceptable to them, and that now is the time to normalize relations with Israel, it will significantly undercut the forces of fundamentalism, militarism and reaction, giving breathing space to those progressive voices that cannot be heard today – including those in Israel. Israel, of course, would also have to resolve the issue of the Golan Heights, which Syria has been asking it to do for years. Despite the neocon rhetoric to the contrary, anyone familiar with the Middle East knows that such a dynamic is not only possible but would progress at a surprisingly rapid pace.

The problem is Israel in both its pre- and post-state forms, which for the past 100 years has steadfastly refused to recognize the national existence and rights of self-determination of the Palestinian people. Time and again it has said “no” to any possibility of genuine peace making, and in the clearest of terms. The latest example is the Convergence Plan (or Realignment) of Ehud Olmert, which seeks to end the conflict forever by imposing Israeli control over a “sovereign” Palestinian pseudo-state. “Israel will maintain control over the security zones, the Jewish settlement blocs, and those places which have supreme national importance to the Jewish people, first and foremost a united Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty,” Olmert declared at the January 2006 Herzliya Conference. “We will not allow the entry of Palestinian refugees into the State of Israel.” Olmert’s plan, which he had promised to implement just as soon as Hamas and Hezbollah were dispensed with, would have perpetuated Israeli control over the Occupied Territories. It could not possibly have given rise to a viable Palestinian state. While the “Separation Barrier,” Israel’s demographic border to the east, takes only 10-15% of the West Bank, it incorporates into Israel the major settlement blocs, carves the West Bank into small, disconnected, impoverished “cantons” (Sharon’s word), removes from the Palestinians their richest agricultural land and one of the major sources of water. It also creates a “greater” Israeli Jerusalem over the entire central portion of the West Bank, thereby cutting the economic, cultural, religious and historic heart out of any Palestinian state. It then sandwiches the Palestinians between the Wall/border and yet another “security” border, the Jordan Valley, giving Israel two eastern borders. Israel would retain control of all the resources necessary for a viable Palestinian state, and for good measure Israel would appropriate the Palestinians’ airspace, their communications sphere and even the right of a Palestinian state to conduct its own foreign policy.

This plan is obviously unacceptable to the Palestinians – a fact Olmert knows full well – so it must be imposed unilaterally, with American assistance. But who cares? We refused to talk genuinely with Arafat, refused to speak at all with Abu Mazen and currently boycott entirely the elected Hamas government, arresting or assassinating those associated with it. And if “Convergence” doesn’t fly this time around, well, maintaining the status quo while building settlements has been an effective policy for the past four decades and can be extended indefinitely. True, Israel has descended into blind, pointless violence – the Lebanon War of 2006 and, as this is being written, an increasingly violent assault on Gaza. But the Israeli public has accepted Barak’s line that there is no “partner for peace.” So if there is any discontent among the voters, they are more likely to throw out the “bleeding heart” liberal left and bring in the right with its failed doctrine of military-based security.

Why? If Israelis truly crave peace and security – “the right to be normal,” as Olmert put it recently – then why haven’t they grabbed, or at least explored, each and every opportunity for resolving the conflict? Why do they continually elect governments that aggressively pursue settlement expansion and military confrontation with the Palestinians and Israel’s neighbors even though they want to get the albatross of occupation off their necks? Why, if most Israelis truly yearn to “separate” from the Palestinians, do they offer the Palestinians so little that separation is simply not an option, even if the Palestinians are willing to make major concessions? “The files of the Israeli Foreign Ministry,” writes the Israeli-British historian Avi Shlaim in The Iron Wall (2001:49), “burst at the seams with evidence of Arab peace feelers and Arab readiness to negotiate with Israel from September 1948 on.” To take just a few examples of opportunities deliberately rejected:

• In the spring and summer of 1949, Israel and the Arab states met under the auspices of the UN’s Palestine Conciliation Committee (PCC) in Lausanne, Switzerland. Israel did not want to make any territorial concessions or take back 100,000 of the 700,000 refugees demanded by the Arabs. As much as anything else, however, was Ben Gurion’s observation in a cabinet meeting that the Israeli public was “drunk with victory” and in no mood for concessions, “maximal or minimal,” according to Israeli negotiator Elias Sasson.

• In 1949 Syria’s leader Husni Zaim openly declared his readiness to be the first Arab leader to conclude a peace treaty with Israel – as well as to resettle half the Palestinian refugees in Syria. He repeatedly offered to meet with Ben Gurion, who steadfastly refused. In the end only an armistice agreement was signed.

• King Abdullah of Jordan engaged in two years of negotiations with Israel but was never able to make a meaningful breakthrough on any major matter before his assassination. His offer to meet with Ben Gurion was also refused. Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett commented tellingly: “Transjordan said – we are ready for peace immediately. We said – of course, we too want peace, but we cannot run, we have to walk.” Three weeks before his assassination, King Abdullah said: “I could justify a peace by pointing to concessions made by the Jews. But without any concessions from them, I am defeated before I even start.”

• In 1952-53 extensive negotiations were held with the Syrian government of Adib Shishakli, a pro-American leader who was eager for accommodation with Israel. Those talks failed because Israel insisted on exclusive control of the Sea of Galilee, Lake Huleh and the Jordan River.

• Nasser’s repeated offers to talk peace with Ben Gurion, beginning soon after the 1952 Revolution, finally ended with the refusal of Ben Gurion’s successor, Moshe Sharett, to continue the process and a devastating Israeli attack (led by Ariel Sharon) on an Egyptian military base in Gaza.

• In general, Israel’s post-war inflexibility was due to its success in negotiating the armistice agreements, which left it in a politically, territorially and militarily superior position. “The renewed threat of war had been pushed back,” writes Israeli historian Benny Morris in his book Righteous Victims. “So why strain to make a peace involving major territorial concessions?” In a cable to Sharett, Ben Gurion stated flatly what would become Israel’s long-term policy, essentially valid until today: “Israel will not discuss a peace involving the concession of any piece of territory. The neighboring states do not deserve an inch of Israel’s land…We are ready for peace in exchange for peace.” ln July, 1949, he told a visiting American journalist, “I am not in a hurry and I can wait ten years. We are under no pressure whatsoever.” Nonetheless, this period saw the emergence of the image of the Arab leaders as intractable enemies, curried so carefully by Israel and representing such a powerful part of the Israeli framing. Morris (1999: 268) summarizes it succinctly and bluntly:

For decades Ben-Gurion, and successive administrations after his, lied to the Israeli public about the post-1948 peace overtures and about Arab interest in a deal. The Arab leaders (with the possible exception of Abdullah) were presented, one and all, as a recalcitrant collection of warmongers, hell-bent on Israel’s destruction. The recent opening of the Israeli archive offers a far more complex picture.

• In late 1965 Abdel Hakim Amer, the vice-president and deputy commander of the Egyptian army invited the head of the Mossad, Meir Amit, to come to Cairo. The visit was vetoed after stiff opposition from Isser Harel, Eshkol’s intelligence advisor. Could the 1967 war have been avoided? We’ll never know.

• Immediately after the 1967 war, Israel sent out feelers for an accommodation with both the Palestinians of the West Bank and with Jordan. The Palestinians were willing to enter into discussion over peace, but only if that meant an independent Palestinian state, an option Israel never even entertained. The Jordanians were also ready, but only if they received full control over the West Bank and, in particular, East Jerusalem and its holy places. King Hussein even held meetings with Israeli officials but Israel’s refusal to contemplate a full return of the territories scuttled the process. The annexation of a “greater” Jerusalem area and immediate program of settlement construction foreclosed any chance for a full peace.

• In 1971 Sadat sent a letter to the UN Jarring Commission expressing Egypt’s willingness to enter into a peace agreement with Israel. Israeli acceptance could have prevented the 1973 war. After the war Golda Meir summarily dismissed Sadat’s renewed overtures of peace talks.

• Israel ignored numerous feelers put out by Arafat and other Palestinian leaders in the early 1970s expressing a readiness to discuss peace with Israel.

• Sadat’s attempts in 1978 to resolve the Palestine issue as a part of the Israel-Egypt peace process that were rebuffed by Begin who refused to consider anything beyond Palestinian “autonomy.”

• In 1988 in Algiers, as part of its declaration of Palestinian independence, the PLO recognized Israel within the Green Line and expressed a willingness to enter into discussions.

• In 1993, at the start of the Oslo process, Arafat and the PLO reiterated in writing their recognition of Israel within the 1967 borders (again, on 78% of historic Palestine). Although they recognized Israel as a “legitimate” state in the Middle East, Israel did not reciprocate. The Rabin government did not recognize the Palestinians’ national right of self-determination, but was only willing to recognize the Palestinians as a negotiating partner. Not in Oslo nor subsequently has Israel ever agreed to relinquish the territory it conquered in 1967 in favor of a Palestinian state despite this being the position of the UN (Resolution 242), the international community (including, until Bush, the Americans), and since 1988, the Palestinians.

• Perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of all was the undermining by successive Labor and Likud governments of any viable Palestinian state by doubling Israel’s settler population during the seven years of the Oslo “peace process” (1993-2000), thus effectively eliminating the two-state solution.

• In late 1995, Yossi Beilin, a key member of the Oslo negotiating team, presented Rabin with the “Stockholm document” (negotiated with Abu Mazen’s team) for resolving the conflict. So promising was this agreements that Abu Mazen had tears in his eyes when he signed off on it. Rabin was assassinated a few days later and his successor, Shimon Peres, turned it down flat.

• Israel’s dismissal of Syrian readiness to negotiate peace, repeated frequently until this day, if Israel will make concessions on the occupied Golan Heights.

• Sharon’s complete disregard for the Arab League’s 2002 offer of recognition, peace and regional integration in return for relinquishing the Occupation.

• Sharon’s disqualification of Arafat, by far the most congenial and cooperative partner Israel ever had, and the last Palestinian leader who could “deliver,” and his subsequent boycott of Abu Mazen.

• Olmert declared “irrelevant” the Prisoners’ Document in which all Palestinian factions, including Hamas, agreed on a political program seeking a two-state solution – followed by attempts to destroy the democratically-elected government of Hamas by force; and on until this day when

• In September and October 2006 Bashar Assad made repeated overtures for peace with Israel, declaring in public: “I am ready for an immediate peace with Israel, with which we want to live in peace.” On the day of Assad’s first statement to that regard, Prime Minister Olmert declared, “We will never leave the Golan Heights,” accused Syria of “harboring terrorists” and, together with his Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni, announced that “conditions are not ripe for peace with Syria.”

To all this we can add the unnecessary wars, more limited conflicts and the bloody attacks that served mainly to bolster Israel’s position, directly or indirectly, in its attempt to extend its control over the entire land west of the Jordan: The systematic killing between 1948-1956 of 3000-5000 “infiltrators,” Palestinian refugees, mainly unarmed, who sought mainly to return to their homes, to till their fields or to recover lost property; the 1956 war with Egypt, fought partly in order to prevent the reemergence onto the international agenda of the “Palestine Problem,” as well as to strengthen Israel militarily, territorially and diplomatically; military operations against Palestinian civilians beginning with the infamous killings in Sharafat, Beit Jala and most notoriously Qibia, led by Sharon’s Unit 101. These operations continue in the Occupied Territories and Lebanon until this day, mainly for purposes of collective punishment and “pacification.” Others include the campaign, decades old, of systematically liquidating any effective Palestinian leader; the three wars in Lebanon (Operation Litani in 1978, Operation Peace for the Galilee in 1982 and the war of 2006); and more.

Lurking behind all these military actions, be they major wars or “targeted assassinations,” is the consistent and steadfast Israeli refusal (in fact extending back to the pre-Zionist days of the 1880s) to deal directly and seriously with the Palestinians. Israel’s strategy until today is to bypass and encircle them, making deals with governments that isolate and, unsuccessfully so far, neutralize the Palestinians as players. This was most tellingly shown in the Madrid peace talks, when Israel only allowed Palestinian participation as part of the Jordanian delegation. But it includes the Oslo “peace process” as well. While Israel insisted on a letter from Arafat explicitly recognizing Israel as a “legitimate construct” in the Middle East, and later demanded a specific statement recognizing Israel as a Jewish state (both of which it got), no Israeli government ever recognized the collective rights of the Palestinian people to self-determination. Rabin was forthright as to the reason: If Israel recognizes the Palestinians’ right to self-determination, it means that a Palestinian state must by definition emerge – and Israel did not want to promise that (Savir 1998:47). So except for vague pronouncements about not wanting to rule over another people and “our hand outstretched in peace,” Israel has never allowed the framework for genuine negotiations. The Palestinians must be taken into account, they may be asked to react to one or another of our proposals, but they are certainly not equal partners with claims to the country rivaling ours. Israel’s fierce response to the eruption of the second Intifada, when it shot more than a million rounds, including missiles, into civilian centers in the West Bank and Gaza despite the complete lack of shooting from the Palestinian side during the Intifada’s first five days, can only be explained as punishing them for rejecting what Barak tried to impose on them at Camp David, disabusing them of the notion that are equals in deciding the future of “our” country. We will beat them, Sharon used to say frequently, “until they get ‘the message’.” And what is the “message”? That this is our country and only we Israeli Jews have the prerogative of deciding whether and how we wish to divide it.

Non-Constraining Conflict Management

The irrelevance of the Palestinians to Israeli policy-makers is merely a localized expression of an overall assumption that has determined Israeli policy towards the Arabs since the founding of the state. Israel, Prime Ministers from Ben Gurion to Olmert have asserted, is simply too strong for the Arabs to ignore. We therefore cannot make peace too soon. Once we get everything we want, the Arabs will still be willing to sue for peace with us. The answer, then, to the apparent contradiction of why Israel claims it desires peace and security and yet pursues policies of conflict and expansion has four parts.

(1) Territory and hegemony trump peace. As Ben Gurion disclosed years ago, Israel’s geo-political goals take precedence over peace with any Arab country. Since a state of non-conflict is even better than peace (Israel has such a relationship with Syria, with whom it hasn’t fought for 34 years, and is thereby able to avoid the compromises associated with peace that might threaten its occupation of the Golan Heights), Israel makes “peace” only with countries that acquiescence to its expansionist agenda. Jordan gave up all claims to the West Bank and East Jerusalem and has even ceased to actively advocate for Palestinian rights. Peace with Egypt, it is true, cost Israel the Sinai Peninsula, but it left its occupation of Gaza and the West Bank intact. Differentiating between those parts of the Arab world with which it wants an actual peace agreement, those with which it needs merely a state of non-conflict and those which it believes it can control, isolate and defeat creates a situation of great flexibility, allows Israel to employ the carrot or the stick according to its particular agenda at any particular time.

Israel can pursue this strategy today only because of the umbrella, political, military and financial, provided by the United States. This is rooted in many different sources including the influence of the organized Jewish community and the Christian fundamentalists on domestic politics and the Congress most obviously. Bipartisan and unassailable support for Israel, however, arises from Israel’s place in the American arms industry and the US’ defense diplomacy. Since the mid-1990s Israel has specialized in developing hi-tech components for weapons systems, and in this way it has also gained a central place in the world’s arms and security industries. One could look at Israel’s suppression of the Intifadas, its attempted pacification of the Occupied Territories and occasional combat with the likes of Hezbollah as valuable opportunities in almost laboratory-like conditions to develop useful weaponry and tactics. This has made it extremely valuable to the West. In fact, Israel is among the five largest exporters of arms in the world, and is poised to overtake Russia as #2 in just a few years (based on Jane’s assessment, May 2, 2006). The fact that it has discrete military ties with many Muslim countries, including Iran, adds another layer of rationality to its guiding assumption that a separate peace with Arab states is achievable without major concessions to the Palestinians. If any state significantly challenges Israeli positions, Israel can pull rank as the gatekeeper to American military programs, including to some degree the US defense industry, and thus to major sources of hi-tech research and development, a formidable position indeed.

(2) A militarily defined security doctrine. Israel’s concept of “security” has always been so exaggerated that it leaves no breathing space whatsoever for the Palestinians, thus eliminating any viable resolution of the conflict. This reflects, of course, its traditional reliance on overwhelming military superiority (the “qualitative edge”) over the Arabs. So overwhelming is it perceived – despite its near-disaster in the 1973 war, its failure to pacify the Occupied Territories and, most recently, its failure against Hezbollah in Lebanon – that it precludes any need for accommodation or genuine negotiations, let alone meaningful concessions to the Palestinians. Several Israel scholars, including ex-military officials, have written on the preponderance of the military in formulating government policy. Ben Gurion’s linking the concept of nation building with that of a nation-in-arms, writes Yigal Levy (reviewing Yoram Peri’s recent book Generals in the Cabinet Room: How the Military Shapes Israeli Policy), made the army an instrument for maintaining a social order that rested on keeping war a permanent fixture.

The centrality of the army depends on the centrality of war…But the moment the political leadership opted to create a ‘mobilized,’ disciplined and inequitable society by turning the army into the ‘nation builder’ and making war a constant, the politicians became dependent on the army. It was not just dependence on the army as an organization, but on military thinking. The military view of political reality has become the main anchor of Israeli statesmanship, from the victory of Ben Gurion and his allies over Moshe Sharett’s more conciliatory policies in the 1950s, through the occupation as a fact of life from the 1960s, to the current preference for another war in Lebanon over the political option (Ha’aretz August 25, 2006).

Ze’ev Maoz, in an article entitled “Israel’s Nonstrategy of Peace,” argues that

Israel has a well-developed security doctrine [but] does not have a peace policy…Israel’s history of peacemaking has been largely reactive, demonstrating a pattern of hesitancy, risk-avoidance, and gradualism that stands in stark contrast to its proactive, audacious, and trigger-happy strategic doctrine…The military is essentially the only government organization that offers policy options – typically military plans – at times of crisis. Israel’s foreign ministry and diplomatic community are reduced to public relations functions, explaining why Israel is using force instead of diplomacy to deal with crisis situations (Tikkun 21(5), September 2006: 49-50).

Again, this approach to dealing with the Arabs is not recent: It is found throughout the entire history of Zionism and has been dominant in the Yishuv/Israeli leadership from the time of the Arab “riots” and the recommendations for partition from the Peel commission in 1937 until this day, with a few very brief interruptions: Sharett (1954-55), Levi Eshkol (1963-69) and, perhaps, Rabin in his Oslo phase (1992-95). Sharett labeled it the camp of the military “activists,” and in 1957 described it as follows:

The activists believe that the Arabs understand only the language of force…The State of Israel must, from time to time, prove clearly that is it strong, and able and willing to use force, in a devastating and highly effective way. If it does not prove this, it will be swallowed up, and perhaps wiped off the face of the earth. As to peace – this approach states – it is in any case doubtful; in any case very remote. If peace comes, it will come only if [the Arabs] are convinced that this country cannot be beaten….If [retaliatory] operations…rekindle the fires of hatred, that is no cause for fear for the fires will be fueled in any event (Morris, 1999: 280).

Feeling that its security is guaranteed by its military power and that a separate peace (or state of non-conflict) with each Arab state is sufficient, Israel allows itself an expanded concept of “security” that eliminates a negotiated settlement. Thus Israel defines the conflict with the Palestinians just as the US defines its War on Terror: As an us-or-them equation where “they” are fundamentally, irretrievably and permanently our enemies. It is no longer a political conflict, and thus it has no solution. Israel’s security, in this view, can be guaranteed only in military terms, or until each and every one of “them” [the Palestinians] is either dead, in prison, driven out of the country or confined to a sealed enclave. This is why rational attempts to resolve the conflict based on mutual interests, identifying the sources of the conflict and negotiating solutions has proven futile all these years. Israel’s guiding agenda and principles have nothing whatsoever to do with either the Palestinians or actual peace. They are rooted instead in an uncompromising project of creating a purely Jewish space in the entire Land of Israel, with closed islands of Palestinians. Even Israel’s most ardent supporters – organized American Jewry, for instance – do not grasp this (Christian fundamentalists and neocons do, and its just fine with them). The claim made by these “pro-Israel” supporters and, indeed, by Israel itself, that Israel has always sought peace and has been rebuffed by Arab intransigence, is actually the opposite of the case. Again, Israel is seeking a proprietorship and regional hegemony that can only be achieved unilaterally, rendering negotiations superfluous and irrelevant. Like the Zionist ideology itself, Israel’s security doctrine is self-contained, a closed circuit. That’s why peace-making efforts over the years, Israeli as well as foreign, have failed miserably. If the assumption – encouraged by Israel – is that the conflict can be resolved through diplomatic means, then Israel can justly be accused of acting in bad faith. Israel and its interlocutors are essentially talking past each other.

The prominence (one is tempted to say “monopoly”) of the military in political policy-making explains the mystery of why Labor in the post-Ben Gurion era chose territorial expansion over peace. Uri Savir, the head of Israel’s Foreign Ministry under Rabin and Peres and a chief negotiator in the Oslo process, provides a glimpse into this dynamic in his book The Process (1998:81, 99, 207-208). After the Declaration of Principles between Israel and the Palestinians was signed on the White House lawn in September 1993

Rabin chose a new team of negotiators. Led by Deputy Chief of Staff Gen. Amnon Shahak, it was composed mostly of military officers. When the military grumbled bitterly at having been shut out of the Oslo talks, Rabin…did not reject the criticism…That Israel’s approach should be dictated by the army invariably made immediate security considerations the dominant one, so that the fundamentally political process had been subordinated to short-term military needs.

In Grenada, Peres had painstakingly explained to Arafat Israel’s stand on security, especially external security and the border passages. “Mr. Chairman, I’m going to give you the straight truth, without embellishment,” he said…We will not compromise on the operational side of controlling the border passages [to Jordan and Egypt]. We’re concerned about the smuggling of weapons. Ten pistols can make for many victims,” he stressed. “This is absolutely vital to our security.”

Arafat, who translated this straight talk into a vision of Palestinians caged in on all sides, replied: “I cannot go for a Bantustan….”

In the end, Israel’s security doctrine generally prevailed. Would compliance with Arafat’s demand for more power and responsibility have improved Israel’s security? The truth is, we will never know….

Now the bureaucrats and the officers who ruled the Palestinians had been asked to pass on their powers to their “wards”…Some of these administrators found it almost unbearable to sit down in Eilat with representatives of their “subjects.” We had been engaged in dehumanization for so long that we really thought ourselves “more equal” – and at the same time the threatened side, therefore justifiably hesitant. The group negotiating the transfer of civil powers did not rebel against their mandate, but whenever we offered a concession or a compromise, our people tended to begin by saying” “We have decided to allow you…”

“Security” became ever more constrictive as right-wing soldiers and security advisors began moving into the highest echelons of the military and political establishments during the years of Likud rule. Fourteen of the first fifteen Chiefs of Staff were associated with the Labor Party; the last three – Shaul Mofaz, Moshe Ya’alon and Dan Halutz – are associated with the right wing of the Likud, a mix of ideology and militarism that reinforces a concept of security that, even if sincerely held, cannot create the space needed for a viable Palestinian state.

(3) Israel as a self-defined bastion of the West in the Middle East. Israel’s European orientation, including a view of the Arab world as a mere hinterland offering Israel little of value, explains why Israel does not place more importance pursuing peace with its neighbors. Israel does not consider itself a part of the Middle East and has no desire whatsoever to integrate into it. If anything, it sees itself as a Middle Eastern variation of Singapore. Like Singapore, it seeks a correct relationship with its hinterland, but views itself as a service center for the West, to which its economy and political affiliations are tied. (Israel, we might note, has built the Singaporean army into what it is today, the strongest military force in Southeast Asia.) That means it lacks the fundamental motivation to achieve any form of regional integration, as evidenced by its off-hand dismissal of the Saudi Initiative of 2002 that, with the backing of the Arab League, offered Israel recognition, peace and regional integration in return for relinquishing the Occupation. And finally,

(4) The immaterial Palestinians. Israel believes that it can achieve a separate peace with countries of the Arab and Muslim worlds (and maintain its overall strong international position) without reference to the Palestinians. Not with the peoples, it is true; that would require a degree of concession to the Palestinians “on the ground” beyond which Israel is willing to go. Knowing this yet having little interest in either the Palestinian people or the Muslim masses, Israel is willing to limit its state of peace/non-conflict with governments – Egypt, Jordan, an emerging Iraq (although Israel is arming the Kurds), the Gulf states, the countries of North Africa (Libya included), Pakistan, Indonesia and some Muslim African countries. In the view of Israeli leaders surveying with satisfaction the political landscape, the notion that Israel is too strong to ignore seems to hold true.

Though it has sustained some serious hits in Lebanon, at the moment Israel is flying high with its central place in the American neocon agenda of consolidating American Empire, its key role in what the Pentagon calls “The Long War” to ensure American hegemony, remains, despite growing doubts over Israel’s ability to “deliver.” Whether or not US policy has been “Israelized” or the “strategic alliance” between the two countries merely rests on perceived common interests and services Israel can offer the US, the Bush Administration has provided Israel with a window of opportunity it is exploiting to the hilt. Despite the Lebanese setback, Israeli leaders still believe they can “win,” they can beat the Palestinians, engineer Israel’s permanent control over the Occupied Territories and achieve enough peace with enough of the Arab and Muslim worlds. That is what Olmert’s “Convergence Plan” (now temporarily shelved) is all about, and why he has resolved to implement it while Bush is still in office. Israel’s security, then, rests in that broad sphere defined by military might, services provided to the US military, the uncritical support of the American Congress, its military diplomacy including arms sales, Israel’s central role in the neocon agenda, its ability to parley European guilt over the Holocaust into political support, its ability to manipulate Arab and Muslim governments and its ability to suppress Palestinian resistance.

So what’s wrong with this picture? Nothing, unless one truly wants peace, security and “the right to be normal” – and unless considerations such as justice and human rights enter into the equation. From a purely utilitarian perspective, Israel is a tremendous success. Perhaps the most hopeful sign of Israel’s “normalization” is its acceptance by most of the Arab and Muslim world, best illustrated by the very Saudi Initiative Israel so summarily ignored. But this also pinpoints the problem. The Saudi/Arab League offer was contingent upon Israel’s relinquishing the Occupation, something it is not prepared to do. True to form, Israel responded to the offer “on the ground” rather than through diplomatic channels. Sharon carried out his plan of “disengagement” from Gaza explicitly to ensure Israel’s permanent and unassailable rule over the West Bank and East Jerusalem, while his successor Olmert vigorously pushed a plan under which the Occupation would be transformed into a permanent state of Israeli control. All this conforms to Israeli policy going back to Ben Gurion which asserts that if Israel limits its aim to achieving a modus vivendi with the Arab and Muslim worlds rather than full-fledged peace, it can ensure its security while retaining control over the land west of the Jordan River. To be sure, occasional spats will erupt such as those in Gaza or with the Hezbollah in Lebanon. Israel might even be called upon to do America’s dirty work in Iran, as it played its role (limited as it was) in Iraq. But those (or at least this was the thinking before the Lebanese debacle) are easily contained, American co-opting of Egypt and Jordan providing the necessary cushion.

This Israeli realpolitik rests on an extremely pragmatic approach to the conflict akin to what the British termed “muddling through.” If Israel’s goal was to resolve the conflict with the Palestinians and seek genuine peace and regional integration, it could easily have adopted policies that would have achieved that, probably long ago. The goal, however, is conflict management, maintaining the “status quo” in perpetuity, and not conflict resolution. Muddling through well suits Israel’s attempt to balance the unbalance-able: expanding territorially at the expense of the Palestinians while still maintaining an acceptable level of security and “quiet.” It enables Israel to meet each challenge as it arises rather than to lock itself into a strategy or set of policies that fail to take into account unexpected developments. Yesterday we tried Oslo; today we’ll hit Gaza and Lebanon, tomorrow “convergence.”

It may not look rational or neat, but conflict management means going with the flow; staying on top of things, knowing where you are going and having contingency plans always at the ready to take advantage of any opening, and dealing with events as they happen. Not long-term strategies but a vision implemented in many often imperceptible stages over time, under the radar so as to attract as little attention or opposition as possible, realized through short-term initiatives like the Convergence Plan which progressively nail down gains “on the ground.”

If this analysis is correct, Israel is willing to settle for peace-and-quiet rather than genuine peace, for management of the conflict rather than closure, for territorial gains that may perpetuate tensions and occasional conflicts in the region, but do not jeopardize Israel’s essential security. Declaring “the right to be normal” becomes a PR move designed to blame the other side and cast Israel as the victim; it is not something that Israeli leaders sincerely expect. Indeed, their very policies are based on the assumption that functional normality – an acceptable level of “quiet,” the economy doing well, a fairly normal existence for an insulated Israeli public most of the time – is a preferred status to the concessions required for a genuine, and attainable, peace.

What About the Battered And Exhausted Israeli Public?

The Jewish Israeli public only partially buys into all this. It would prefer actual peace and normalization to territorial gains in the Occupied Territories, though it definitely prefers separation from the Arab world to regional integration. If Israelis prefer peace to continued conflict with the Palestinians and their Arab neighbors, why, then, do they vote for governments that pursue the exact opposite, that prefer conflict management and territory to peace? Mystification of the conflict on the part of Israeli leaders plays a large role, just as it does in the “clash of civilizations” discourse in other Western countries. Since Israel’s strategy of enduring a certain level of conflict as an acceptable price for territorial expansion would not be tolerated if it was stated in those terms, successive Israel governments from Ben Gurion to Olmert instead convinced the public that there is simply no political solution. The Arabs are our intransigent and permanent enemies; we Israeli Jews, the victims, have sought only peace and a normal existence, but in vain. And that’s just the way it is. As Yitzhak Shamir put it so colorfully: “The Arabs are the same Arabs, the Jews are the same Jews and the sea [into which the former seek to throw the latter] is the same sea.” Israel effectively adopted the clash of civilizations notion years before Samuel Huntington.

This manipulative framing of the conflict also fashions discourse in a way that prevents the public from “getting it.” Israel’s official national narrative supplies a coherent, compelling justification for doing whatever we like without being held accountable – indeed, it renders all criticism of us as “anti-Semitism.” The self-evident framing which determines the parameters of all political, media and public discussion goes something like this:

The Land of Israel belongs exclusively to the Jewish people; Arabs (the term “Palestinian” is seldom used) reside there by sufferance and not by right. Since the problem is implacable Arab hatred and terrorism and the Palestinians are our permanent enemies, the conflict has no political solution. Israel’s policies are based on concerns for security. The Arabs have rejected all our many peace offers; we are the victim fighting for our existence. Israel therefore is exempt from accountability for its actions under international law and covenants of human rights.

Any solution, then, must leave Israel in control of the entire country. Any Palestinian state will have to be truncated, non-viable and semi-sovereign. The conflict is a win-lose proposition: either we “win” or “they” do. The answer to Israel’s security concerns is a militarily strong Israel aligned with the United States.

One of this framing’s most glaring omissions is the very term “occupation.” Without that, debate is reduced solely to what “they” are doing to us, in other words, to seemingly self-evident issues of terrorism and security. There are no “Occupied Territories” (in fact, Israel officially denies it even has an occupation), only Judea and Samaria, the heart of our historic homeland, or strangely disembodied but certainly hostile “territories.” Quite deliberately, then, Israelis are studiously ignorant of what is going on in the Occupied Territories, whether in terms of settlement expansion and other “facts” on the ground or in terms of government policies. One can listen to the endless political talk shows and commentaries in the Israeli media without ever hearing a reference to the Occupation. Pieces of it yes: Settlements, perhaps; the Separation Barrier (called a “fence” in Israel) occasionally; almost never house demolitions or references to the massive system of Israel-only highways that have incorporated the West Bank irreversibly into Israel proper, never the Big Picture. Although Olmert’s Convergence Plan, which is of fundamental importance to the future of Israelis, is based upon the annexation of Israel’s major settlement blocs, the public has never been shown a map of those blocs and therefore has no clear idea of what is actually being proposed or its significance for any eventual peace. But that is considered irrelevant anyway. When, very occasionally, Israelis are confronted by the massive “facts of the ground,” they invoke the mechanism of minimization: OK, they say, we know all that, but nothing is irreversible, the fence and the settlements can be dismantled, all options continue to be open. In this way they do not have to deal with the enormity of what they have created, one system for two peoples, which, if the status quo cannot be maintained forever, can only lead to a single bi-national state or to apartheid, confining the Palestinians to a truncated Bantustan. While the official narrative deflects public attention from the sources of the conflict, minimization relieves Israelis of responsibility for either perpetuating or resolving it.

Framing, then, becomes much more than a PR exercise. It becomes an essential element of defense in insulating the core of the conflict – the Occupation itself, the pro-active policies of settlement that belie the claims of “security,” and Israel’s responsibility as the occupying power – from both public scrutiny and public discussion. Defending that framing is therefore tantamount to defending Israel’s very claim to the country, the very “moral basis” of Zionism we Israelis constantly invoke. No wonder it is impossible to engage even liberal “pro-Israeli” individuals and organizations in a substantive and genuine discussion of the issues at hand.

One result of such discursive processes is the disempowerment of the Israeli public. If, in fact, there is no solution, then all that’s left is to hunker down and carve out as much normality as possible. For Israelis the entire conflict with the Arabs has been reduced to one technical issue: How do we ensure our personal security? Since conflict management assumes a certain level of violence, the public has entered into a kind of deal with the government: You reduce terrorism to “acceptable” levels, and we won’t ask how you do it. In a sense the public extends to the government a line of credit. We don’t care how you guarantee our personal security. Establish a Palestinian state in the Occupied Territories if you think that will work; load the Arabs on trucks and transfer them out of the country; build a wall so high that, as someone said, even birds can’t fly over it. We, the Israeli Jewish public, don’t care how you do it. Just do it if you want to be re-elected.

This is what accounts for the apparent contradiction between the public will and the policies of the governments it elects. That explains how in 1999 Barak was elected with a clear mandate to end the conflict, and when he failed and the Intifada broke out, that same public, in early 2001, elected his mirror opposite, Ariel Sharon, the architect of Israel’s settlement policies who eschewed any negotiations at all. Israelis are willing to sacrifice peace for security – and do not see the contradiction – because true “peace” is considered unattainable. In fact, “peace” carries a negative political connotation amongst most Israelis. It denotes concessions, weakness, increased vulnerability. Israel’s unique electoral system, in which voters cast their ballots for parties rather than candidates and end up either with unwieldy coalition governments incapable of formulating and pursuing a coherent policy, only adds to the public’s disempowerment and its unwillingness to entrust any government with a mandate to arrive at a final settlement with the Arabs.

Because the “situation,” as we call it, has been reduced to a technical problem of personal security without political solution, Israelis have become passive, bordering on irresponsible. They have been removed from the political equation altogether. Any attempt to actually resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict (and its corollaries) will have to come from the outside; the Israeli public will simply not make a proactive move in that direction. While the government will obviously oppose such intervention, the Israeli public may actually welcome it – if it is announced by a friend (the US), pronounced authoritatively with little space for haggling (as Reagan did over the sale of AWACs surveillance aircraft to Saudi Arabia in the early 1980s), and couched as originating out of concern for Israel’s security. Israeli Jews may be likened to the whites of South Africa during the last phase of apartheid. The latter had grown accustomed to apartheid and would not themselves have risen up to abolish it. But when international and domestic pressures became unbearable and de Klerk finally said, “It’s over,” there was no uprising, even among the Afrikaners who constructed the regime. I sincerely believe that if cowboy Bush would get up one morning and say to Israel: “We love you, we will guarantee your security, but the Occupation has to end. Period,” that you would hear the sigh of relief from Israelis all the way in Washington.

As it stands, the Israeli leadership thinks we are winning, the people are not so sure but are too disinformed and cowed by security threats (bogus and real) to act, and the peace movement has been reduced to a pariah few crying out in the wilderness. Given the support Israel receives from the US in return for services rendered to the Empire, Europe’s quiescent complicity and Palestinian isolation, the question remains whether Israel’s strategy of conflict management has not in fact succeeded – again, considerations of justice, genuine peace and human rights aside. Say what you will, the realists can point to almost sixty years during which Israel has emerged as a regional, if not global superpower in firm control of the greater Land of Israel. If Olmert succeeds in implementing his Convergence Plan, the conflict with the Palestinians is over from Israel’s point of view – and we’ve won.

Yet so overwhelming is our military might, so massive and permanent have we made our controlling presence in the Occupied Territories, that we have fatally overplayed our hand. Ben Gurion’s formula worked. We now have everything we want – the entire Land of Israel west of the Jordan River – and the Arab governments have sued for peace. But four elements of the equation that Ben Gurion (or Meir or Peres, or Netanyahu, Barak, Sharon, Olmert and all the rest) did not take into account have arisen to fundamentally challenge the paradigm of power:

(1) Demographics. Israel does not have enough Jews to sustain its control over the greater Land of Israel. (Indeed, whether Israel proper can remain “Jewish” is a question, with the Jewish majority down just under 75%, factoring in the Arab population, the non-Jewish Russians and emigration.) Zionism created a strong state, but it did not succeed in convincing Jews to settle it. The Jewish population of Israel represents less than a third of world Jewry; only 1% of American Jews made aliyah. In fact, whenever Jews had a choice – in North Africa, the former Soviet Union, Iraq, Iran, South Africa and Argentina, not to mention all the countries of Europe and North America – they chose not to come to Israel. And it is demographics that is driving Olmert’s Convergence Plan. “It’s only a matter of time before the Palestinians demand ‘one man, one vote’ – and then, what will we do?”, he asked plaintively at the 2004 Herzilya conference. Olmert’s scheme retains control of Israel and the Occupied Territories (in his terms Judea, Samaria and eastern Jerusalem) while doing the only thing possible with the Palestinians who make up half the population – locking them into a truncated Bantustan on a sterile 15-20% of the country.

(2) Palestinians. Israel’s historical policy of ignoring and bypassing the Palestinians can no longer work. Palestinians comprise about half the population of the land west of the Jordan River, all of which Israel seeks to control, and will be a clear majority if significant numbers of refugees are repatriated to the Palestinian Bantustan. Keeping that population under control means that Israel must adopt ever more repressive policies, whether prohibiting Israeli Arab citizens from bringing their spouses and children from the Occupied Territories to live with them in Israel, as recent legislation has decreed, or imprisoning an entire people behind 26-foot concrete walls. Despite Olmert’s assertion that Israelis have a right to live a normal life, normalcy cannot be achieved unilaterally. Neither an Occupation nor a Bantustan nor any other form of oppression can be normalized or routinized; it will always be resisted by the oppressed. Strong as Israel is militarily, it has not succeeded in pacifying the Palestinians over the last 40 years of occupation, 60 years since the Naqba or century since the Zionist movement claimed exclusive patrimony over Palestine and begin to systematically dispossess the indigenous population. The Palestinians today possess one weapon that Israel cannot defeat, that it must one day deal with, and that is their position as gatekeepers. Until the Palestinians signal the wider Arab, Muslim and international communities that they have reached a satisfactory political accommodation with Israel, the conflict will continue and Israel will fail to achieve either closure or normalcy.

(3) The Arab/Muslim peoples. The role of Palestinians as gatekeepers reflects the rise in importance of civil society as a player in political affairs. Israel’s lack of concern over the Arab and Muslim “streets,” its reliance solely on peace-making with governments, indicates a major failure in Israel’s strategic approach to the conflict: Its underestimation of the power of the people. Sentiments such as “We don’t care about making peace with the Arab peoples; correct relations with their governments are enough,” ignore the fragile state of Arab governments created by the rise of Muslim fundamentalism, which in turn has been fueled in large part (though not exclusively, of course) by the Occupation. If Hezbollah has the power to create the instability is has, imagine what will happen if the Muslim Brotherhood seizes power in Egypt. The disproportionate bias towards Israel in American and European policies only fuels and sharpens the “clash of civilizations,” while Israel’s Occupation effectively prevents progressive elements from emerging in the Arab and Muslim worlds. The strategic role played by Palestinians as gatekeepers has a significant effect upon the stability of the entire global system. The Israel-Palestine conflict is no longer a localized one.

(4) International civil society. As we have seen, Israeli leaders, surveying the international political landscape as elected officials do, take great comfort. They believe that, with uncritical and unlimited American support, their country is “winning” its conflict over the Palestinians (and Israel’s other enemies, real and imagined). Like political leaders everywhere, they don’t seriously take “the people” into account. Yet, The People – what is known as international civil society – have some achievements under their belt when it comes to defeating injustice. They forced the American government to enforce the civil rights of black people in the US and to abandon the war in Vietnam. They played major roles in the collapse of South African apartheid, of the Soviet Union and of the Shah’s regime, among many others. Since governments will almost never do the right thing on their own, it was civil society, through the newly established UN, that forced them to accept the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Conventions and a whole corpus of human rights and international law. With the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court at our disposal, as well as other instruments, and as civil society organizes into Social Forums and other forms of action coalitions, major cases of injustice, such as Israel’s Occupation, are becoming less and less sustainable. As the Occupation assumes the proportions of an injustice on the scale of apartheid – a conflict with global implications – Olmert may convince Bush and Blair to support his plan, but the conflict will not be over until two gatekeepers say it is, the Palestinians and the people worldwide.

The Only Way Out: Forcing Israel To Take Responsibility

Israel has only one way out: It must take responsibility for its actions. No more blaming Arafat and Hamas and the Arabs in general. No more playing the victim. No more denying Occupation or the human rights of a people just as lodged into this land as the Jews, if not more so. No more using the military to ensure “our” security. No more unilateralism. Instead, Israel must work with the Palestinians to create a genuine two-state solution. No Geneva Initiative whereby the Palestinians get a non-viable 22% of the country; nor convergence nor realignment nor apartheid. Simply an end of Occupation and a return to the 1967 borders (in which Israel still retains 78% of the country) – or, if a just and viable two-state solution is in fact buried forever under massive Israeli settlement blocs and highways, then another solution. And a just solution to the refugee issue. Over time, the Palestinians – who are greater friends of Israel than any Israeli realizes – might even use their good offices to eventually enter into a regional confederation with the neighboring states (see my article in Tikkun 20[1)]17-21: “Israel in a Middle East Union: A ‘Two-stage’ Approach to the Conflict.”).

This is a tall order, and it will not happen soon. The military’s mobilization of Jewish Israelis has created a remarkably high consensus (85% support the construction of the Wall; 93% supported the recent war in Lebanon), making it impossible for truly divergent views to penetrate. Some of this has to do with overpowering feelings of self-righteousness, combined with the perception of Israel as the victim (and hence having no responsibility for what happens, a party that cannot be held accountable). Disdain towards Arabs also allows Israel to harm Palestinian (and again Lebanese) civilian populations with impunity and no sense of guilt or wrongdoing.

Although Israel has a small but vital peace movement and dissident voices are heard among intellectuals and in the press, the combination of mystification (“there is no partner for peace”), disdain, vilification and dehumanization of the Palestinians, a self-perception of Israelis-as-victims, the supremacy of all-encompassing “security” concerns, and a compelling but closed meta-narrative means that little if any space exists for a public debate that could actually change policy. Because the Israel public has effectively removed itself as a player – except in granting passive support to its political leaders who pursue a program of territorial expansion and conflict management – a genuine, just and sustainable peace will not come to the region without massive international pressure. This is starting to happen as the Occupation assumes global proportions and churches, together with other civil society groups, weigh campaigns of divestment and economic sanctions against Israel – forms of the very nonviolent resistance that the world has been demanding. The Israeli Jewish public, unfortunately, has abrogated its responsibility. Zionism, which began as a movement of Jews to take charge of their lives, to determine their own fate, has ironically become a skein of pretexts serving only to prevent Israelis from taking their fate in their own hands. The “deal” with the political parties has turned Israeli government policies into mere pretexts for oppression, for “winning” over another people, for colluding with American Empire.

The problem with Israel is that, for all the reasons given in this paper, it has made itself impervious to normal political processes. Negotiations do not work because Israeli policy is based on “bad faith.” If Israel’s actual agenda is territorial expansion, retaining control of the entire country west of the Jordan and foreclosing any viable Palestinian state, then any negotiations that might threaten that agenda are put off, delayed or avoided. All Israeli officials and their surrogates – local religious figures, representatives of organized Jewish communities abroad, liberal Zionist peace organizations, intellectuals and journalists defining themselves as “Zionist,” “pro-Israel” public figures in any given country and others – become gatekeepers. In effect – deliberately or not – their essential role is not to engage but to deflect engagement, to “build a fence” around the core Israeli agenda so as to appear to be forthcoming but to actually avert any negotiations or pressures that might threaten Israel’s unilateral agenda.

It’s a win-lose equation. If Ben Gurion’s principle that the Arabs will sue for peace even after we get everything we want, then why compromise? True, Israel could have had peace, security and normalization years ago, but not a “unified” Jerusalem, Judea or Samaria. If the price is continued hostility of the Arab and Muslim masses and no integration into the region, well, that’s certainly something we can live with. In the meantime, we can rely on our military to handle any challenges to either our Occupation or our hegemony that might arise.

This logic carried us through almost to the end, to Olmert’s Convergence Plan that was intended to “end” the Occupation and establish a permanent regime of Israeli dominance. And then Israel hit the wall, a dead-end: The rise of Hamas to power in the Palestinian Authority and the traumatic “non-victory” over Hezbollah. Both those events exposed the fatal flaw of the non-conflict peace policy. The Palestinians are indeed the gatekeepers, and the Arab governments in whom Israel placed all its hopes are in danger of being swept away by a wave of fundamentalism fueled, in large part, by the Occupation and Israel’s open alignment with American Empire. Peace, even a minimally stable non-peace, cannot be achieved without dealing, once and for all, with the Palestinians. The war in Lebanon has left Israel staring into the abyss. The Oslo peace process died six years ago, the Road Map initiative was stillborn and, in the wake of the war, Olmert has announced that his convergence plan, the only political plan the government had, was being shelved for the time being. Ha’aretz commentator Aluf Benn spoke for many Israelis when he reflected:

Cancellation of the convergence plan raises two main questions: What is happening in the territories and what is the point of continuing Olmert’s government? Olmert has no answers. The response to calls to dismiss him is the threat of Benjamin Netanyahu at the helm. But what, exactly, is the difference? Both now propose preservation of the status quo in the territories, rehabilitation of the North and grappling with Iran. At this point, what advantage does the head of state have over the head of the opposition? (Ha’aretz, August 25, 2006)

Without the ability to end or even manage its regional conflicts unilaterally, faced with the limitations of military power, increasingly isolated in a world for whom human rights does matter, yet saddled with a political system that prevents governments from taking political initiative and a public that can only hunker down, Israel finds itself not in a status quo but in a downward spiral of violence leading absolutely nowhere. Even worse, it finds itself strapped to a superpower that itself is discovering the futility of unilateralism in its own Middle East adventures even while encouraging Israel to join in. Still, knowing that governments will not do the right thing without being prodded by the people, the Israeli peace camp welcomes the active intervention of the progressive international civil society. In the end we can only hope that the Israeli mainstream will join us.

The door to peace is still wide open. The Palestinian, Lebanese, Egyptian and Syrian governments have said that war raises new possibilities for peace. Even Peretz said as much, but was forced to backtrack when Tzipi Livni, the Foreign Minister, declared the “time was not ripe” for talks with Syria. Instead the Olmert government appointed the chief of the air force to be its “campaign coordinator” in any possible war with Iran, and then named Avigdor Lieberman, the extremist right-winger who is on record as favoring a attacks on Iran as well as a nuclear strike on Egypt’s Aswan Dam, as Deputy Prime Minister and “Minister of Strategy.”

Israel will simply not walk through that door, period. There is no indication that one of the lessons learned from the Lebanese disaster will be the futility of imposing a military solution on the region. On the contrary, the chorus of protest in Israel in the wake of the war is: Why didn’t the government let the army win? Demands for the heads of Olmert, Peretz and Halutz come from their military failure, not from a failure of their military policy. But instead of demanding a government inquiry as to why Israel lost the war, the sensible Ha’aretz columnist Danny Rubinstein suggests a government inquiry on why Israel has not achieved peace with its neighbors over the past sixty years.

The question then is, will the international community, the only force capable of putting an end to the superfluous destabilization of the global system caused by Israel’s Occupation, step in and finally impose a settlement agreeable to all the parties? So far, the answer appears to be “no,” constrained in large part by America’s view that Israel is still a valuable ally in its faltering “war on terror.” Only when the international community – led probably by Europe rather than the US, which appears to be hopeless in this regard – decides that the price is too high and adopts a more assertive policy towards the Occupation will Israel’s ability to manipulate end. Civil society’s active intervention is crucial. We – Israelis, Palestinians and internationals – can formulate precisely what the large majority of Israelis and Palestinians crave: a win-win alternative to Israel’s self-serving and failed “security” framing based on irreducible human rights. Such a campaign would contribute measurably to yet another critical project: A meta-campaign in which progressive forces throughout the world articulate a truly new world order founded on inclusiveness, justice, peace and reconciliation. If, in the end, Israel sparks such a reframing, if it generates a movement of global inclusiveness and dialogue, then it might, in spite of itself, yet be the “light unto the nations” it has always aspired to be.

(Jeff Halper is the Coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions. He can be reached at jeff@icahd.org).

Misschien is het maar beter ook het niet te vertalen Anja.

Na deze samenvatting van de onwil van alle Israelische regeringen in alle jaren vanaf 1948 om de rechten van de Palestijnen zelfs maar onder ogen te zien moet je wel heel sterk in je schoenen staan om toch nog optimistisch te blijven.

De enige kans voor de Palestijnen is de druk die moet komen van de westerse landen en de VS. Inmiddels heb ik al begrepen dat ook van de democraten daar niets goeds is te verwachten. En helaas staat Europa blijkbaar al net zo onder invloed van de Israelisch, zionistische lobby.

Als iets uit het artikel duidelijk wordt is het wel dat de gekozen Israelische regeringen altijd wel argumenten zullen kunnen vinden om te voorkomen dat er echt onderhandeld moet worden. En er ook geen been in zien de situatie naar hun hand te zetten door het uit de weg ruimen van Palestijns kader als dat nodig lijkt.

Maar misschien ben ik te pessimistisch. Er leven nu eenmaal enkele miljoenen Palestijnen in het gebied. Ze allemaal weg te pesten zal toch een probleem blijven.