Te gast: Gideon Levy

Blood on the hands: Two crimson handprints stain the white wall. The tile floor shines in shades of brown, the walls are painted in white and soft pastels, their new house, after the two previous ones were destroyed by the Israel Defense Forces. The bloody handprints stand as silent testimony on the wall of the staircase that goes up to the second floor. This is where Ruqiya stood, the blood of her dead daughter all over her hands, as she pounded them on the wall in a panic, desperately calling to the neighbors for help. She pounded and pounded, her palms staining the wall, when outside stood a line of terrifying jeeps, on the roof of the building down the street stood the snipers and in the other room Bushra lay dead in a spreading pool of blood, a bullet hole in the center of her forehead.

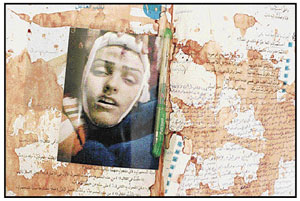

The blood also spilled on her grammar workbook, staining it. Her green pen was also covered with blood; it’s still there, amid the bloody pages. The grammar book of Bushra Bargis (Al-Wahsh), the study material of a girl who was preparing for the Magen pre-matriculation exam, her last exam. Among the pages of the workbook, which has become a kind of memorial book, the family has inserted the death picture: a twisted smile, eyes half-closed and a small hole in the forehead.

Bushra, 17, was killed by a sniper’s bullet aimed at the middle of her forehead as she paced her room, grammar book in hand, memorizing the material for the exam the next day. A direct hit. The lights were on in the room, the shooter must have seen the person at whom he was firing, whose life he was taking with such dreadful ease.

A sniper’s amusement? One bullet in a teenager’s forehead and two bullets in the door of the refrigerator, which is in the new kitchen off of Bushra’s room, a place where the females of the house hid: Ruqiya, her daughter Suqeina, 23, and Suqeina’s three-year-old daughter, Dareen. Two women, a teenaged girl and a toddler in the house where the soldiers thought Abd al-Rahman Al-Wahsh, a wanted man and Bushra’s brother, was hiding.

In stark contrast to the IDF’s version of events, all the eyewitnesses say the occupants were called to leave the house only after the sniper had killed Bushra in cold blood. Logic says it happened that way, too: No teenager would keep studying if soldiers were calling from below to evacuate the house. Three sniper’s bullets, from a distance of about 150 meters, abruptly halted Bushra’s preparations for her last exam.

The Jenin checkpoint. Two IDF soldiers, military policemen, speaking Arabic to each other, wander about here and there with nothing much to do. A rental car approaches the checkpoint and an elderly British tourist gets out. “Do I need to wait here?,” he asks in surprise, believing he has come to a tollbooth. “Where you going?,” Staff-Sergeant Hikmat asks in broken English. “To Jerusalem,” replies the tourist, proffering his rental agency road map as proof and confidently pointing out the shortest route to the capital – through Jenin – of course. The Green Line is dead in the new maps of the rental agencies, and the Briton is beside himself.

True to form, one week the IDF allows us to enter Jenin in our protected vehicle, while the next week it does not, despite all the prior coordination and assurances. No entry this week. A yellow taxi from Jenin quickly takes us into the refugee camp, its driver stunned by the identity of his Jewish passengers. The only hospital in town is still closed because of a strike by workers who have not been paid, and the new road in the rebuilt camp is already strewn with obstacles and potholes.

The IDF enters the camp every night now, sowing fear in the heart of the residents, especially the children. At first there was no resistance and the soldiers would bring out dozens of men, half-clothed, into the night chill. In recent weeks, the armed young men of the camp have decided to greet the jeeps with makeshift bombs – cooking gas canisters that they place by the side of the road, in the heart of the camp. Boom after boom, sounds of explosions and gunfire, every night is a nightmare now, a night without sleep, with children wetting their beds and their anxious, helpless parents.

Saturday night two weeks ago was just such a night. In the afternoon, IDF troops had killed three armed men in the city and the mood was agitated. In her room on the second floor of the renovated house near the camp mosque, Bushra was preparing for her Magen grammar exam. Her father died eight years ago. One brother, Abdullah, was sentenced about five years ago to 23 years in prison. Another brother, Abd al-Aziz, had just been released from two years in administrative detention, held without trial. Soldiers who had come in search of the third brother, Islamic Jihad activist Abd al-Rahman, who has been wanted for the past two years, arrested him instead.

For years, Bushra was the only family member permitted to visit Abdullah in prison. In the past five years his mother has been allowed to visit only six times. Since Bushra was killed, Israel has not allowed Abdullah to even speak on the telephone with his grieving mother. He is in the Ashkelon Prison, where he must have heard about his sister’s killing, and cannot call his mother to comfort her. Abdullah was arrested the same day the IDF killed UNRWA worker Ian Hook, from Britain, in the camp, in November 2002. Four months ago his sister visited him for the last time.

On Saturday morning Bushra took the Magen exam in history. Afterward she went to her old girls’ elementary school for an open house, with performances and refreshments. A few days before Bushra received a prize for her academic achievement: a colorful clock shaped like a castle, with a turret and with flowers in front. The clock has stopped.

In the afternoon she returned home, had something to eat and began studying for Sunday’s grammar exam.

The previous Saturday Bushra and some of her classmates took a little excursion. Here is the photo, which turned out to be the last photograph of Bushra: Four teenaged girls in their striped uniforms and headscarves, gently leaning against one another, hesitantly smiling at the camera, against the backdrop of one of the tourist sites in Wadi al-Badin, on the way to Nablus. The sun’s rays shine through the trees and none of the girls knows that, within a week, this photo will become a memorial picture. Bushra wanted to be a lawyer, in a household where no provider was left.

In the afternoon, Bushra asked her brother to buy her some pens, to make sure she was all set for the test the next day. Abd al-Aziz bought her five cheap pens. One is still stuck inside the bloodstained schoolbook. Later, Bushra and her mother recited the evening prayers and the night prayers, and in between Bushra studied. She had a habit of pacing as she studied, walking back and forth in her room as she memorized material. At about 9 P.M. there was a noise from the street. Ruqiya rushed to the window to locate the source: A long line of jeeps, headlights off, approached the house, which was at the edge of the camp. Bushra quickly picked up her niece, Dareen, who was sleeping on a mattress under the window. She took her into the kitchen, in the interior of the house, to move her away from the eye of the approaching storm. She then returned to her room and resumed her studies, in front of the open window. Everyone else went into the kitchen. The soldiers did not shout at them to evacuate, and the women were certain that they were there because of the disturbances in the city on that deadly day.

Ruqiya and Suqeina, crowded into the kitchen, Dareen asleep on the floor, they suddenly heard a strange sound. To their astonishment, they found two bullets stuck in the refrigerator door. Let’s repeat: The kitchen is deep inside the apartment, on the second floor, and gunfire toward it could only have come from the house down the street, about 150 meters as the crow flies. Soldiers and snipers had hidden in the house down the street before.

At the sight of the two bullets stuck in the refrigerator, Ruqiya called to her daughter, in the next room, and when Bushra did not respond the mother hurried in. Bushra was lying on her back on the floor, in a puddle of blood that was pooling under her head, with a hole in her forehead and the workbook in her hand. She was lying far from the window, in the center of the room. You don’t have to be a ballistics expert to see that there is no way the shots could have come from the jeeps parked outside the house.

Ruqiya knew: Her daughter was dead. She began screaming for help and pounding on the wall of the staircase, and then went up on the roof and yelled for help from there, too. According to the women of the house as well G.Z., a very credible witness who was at the neighbors’, it was only after Ruqiya’s shouts were heard that the soldiers called on the women, through a megaphone, to leave the house. This is a key point. The next day, the IDF would claim that the soldiers told the women to come out and that only Bushra remained inside despite the order.

They went out to the street, at the soldiers’ orders. None of the soldiers left their jeeps that were parked near the house. Bushra was left, bleeding in her room, apparently already dead. “You killed my daughter!,” Ruqiya screamed at the soldiers, pounding on the sides of the armored vehicles, but no one came out to help. She told the soldiers the house was unlocked and they could go enter to search for the wanted man or to see the body of his dead sister, but no one went in.

“Why didn’t they enter the house? Why didn’t they tell us to come out right away? Had they called us before, we would have come right out,” Ruqiya says. The soldiers asked to see Ruqiya’s identity card but she says she refused. She just pleaded for her and her daughter to be allowed back into the house, to see Bushra, but she says the soldiers wouldn’t let her.

About a half hour later, a Palestinian ambulance arrived. The medics went inside and brought Bushra down to the door on a mattress. Her mother, sister and niece stood there, shaking. This scene lasted for about an hour, maybe more, they say. The body lying on a mattress at the entrance to the house, the women standing barefoot and upset in the street, the frightened Dareen in her mother’s arms and Ruqiya’s hands still stained with her daughter’s blood, while the soldiers remained in their jeeps. Suddenly, the soldiers threw smoke grenades and left the way th ey had come, leaving the women of the family with the body.

IDF Spokesman’s response: “In the course of operations of an IDF force that traveled near the Jenin refugee camp, a number of explosive devices were thrown and targeted gunfire was directed against the force a number of times. The force returned fire in the direction of the shooting. An investigation of the incident showed that the force definitively confirmed that shots were fired a number of times from the window of the building. At a nearby window a figure was seen holding a weapon and it was fired upon. After the operation the Coordination and Liaison headquarters received a report of the killing of a Palestinian girl.”

The blood-soaked carpet has been rolled up andtaken up to the roof and laid alongside the satellite dish. The house from which the sniper apparently shot and killed Bushra is visible across the way. A picture of Abdullah, the prisoner, hangs on the wall of the room in which his sister was killed. Her picture will be placed next to his. For now, a very large photo of Bushra, the girl who never made it to her exam on Sunday, rests in its frame.

Dear Anja,

Above anything else, we fully highlight your reviewing such stories that manifestly reflect the unjustifiable Israeli actions against our children, women and youth.

I would like to comment on what happened to Busha whom was killed with no sin by the Israel army whose crimes won’t end…

There are a lot of unoccupied seats but by a wreath or a bag personifying who was sitting there before martyrdom. Those victims have no sins but being Palestinians .

Every one sees Bushra’s face on this picture, he/she will visualize one of his/her children

Fatma