Te gast: Gideon Levy

Haaretz.

Let the chips fall where they may, the saying goes, but this time the chip was a terrifying concrete beam that was sent flying into the air hundreds of meters from a house the IDF bombed in the middle of the night. It landed in the bedroom of a 14-year-old girl, Dahm al-Az Hamad. Sometimes children are killed, but this time the girl was her parents’ only child. Her mother is paralyzed. Sometimes tragedies happen, but the tragedy of the Hamad family is almost too much to describe.

As Dahm al-Az lay in her mother’s embrace, the beam smashed into her frail body and tore it to pieces. Now this long-impoverished and newly bereaved family sits dumbstruck in its tin house in the Brazil refugee camp, at the edge of Rafah. The tin ceiling of the bedroom is still in tatters, the remains of the beam still lie on the floor, while sitting in the plastic chair in the shabby living room, Basama the mother sits and weeps silently. Her wheelchair was also destroyed in the bombing. There is no longer anyone to nurse her, no longer an iota of hope in the home that was suddenly rendered childless. The pilot pressed a button and two powerful bombs, amazingly smart and precise, landed one after the other, sending the beam flying into the air and inflicting a horrific tragedy on the Hamad family, which was already a victim of fate. Regards to the pilot.

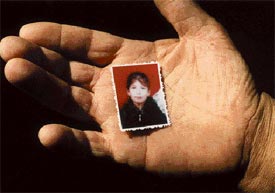

They have only one photograph of their daughter, a tiny eternal remembrance in the form of a blurred passport photo of a small, beautiful little girl, her hair neatly done and a hint of a weak smile on her lips. There is nothing more than that.

Machine gun fire starts at the entrance to Khan Yunis, and all the drivers turn around and leave as fast they can. It is the Al-Masri family against the Abu Tahar family, and there is no one to make them lay down their arms. When we finally reach the Brazil refugee camp, at the southern edge of Rafah in the southern tip of the Gaza Strip, the familiar Grozny-like scenes – this is the most run-down and wretched of all the refugee camps – loom into view. Heaps of ruins, numberless perforated homes are the fruit of years of fighting along the Philadelphi strip, which has not yet come to an end. The Hamads’ home is in the second row of houses and is still standing, opposite the iron fence that separates Egypt and the Gaza Strip. All around it are houses that have long since been blasted into dirt and dust.

A sand trail leads to the house, next to which the family’s laundry flaps in the dry breeze. Dahm al-Az’s bloodstained clothes were buried in the sand. Over the past four years, Basama’s shrunken body was attacked by a paralysis that is progressing at a frightening pace. There is no one in this refugee camp to diagnose her, and the couple has no idea what is afflicting her. What is clear is that her condition is swiftly deteriorating. She is spending her final days in the plastic chair in the living room, unable even to shoo away the flies that pester her. Wearing a red dress, hunched on the white chair, she is barely able to speak. Her whole face contorts as she tries to tell about her only child.

Dahm al-Az was a ninth-grade student who spent most of her time caring for her mother. Ahmed and Basama have no other children – his marriage seven years ago to a second wife, Fadwa, did not change this state of affairs.

On Wednesday, September 27, the girl went to school as usual. She got back at noon and began to nurse her mother as usual. She washed her shriveled body, carried her to the toilet and helped her father’s second wife with the housework. When her mother fell ill, Dahm al-Az’s childhood ended. The month of Ramadan had already begun, and the members of the household were waiting for the sun to set so they could break the daily fast. Afterward the girl washed the dishes and the family continued to sit in the large empty living room. They do not watch television during Ramadan. At 9 P.M. Dahm al-Az went to bed. She slept in the same bed as her incapacitated mother, in a room on the edge of the house. The walls of the room are blue, and it was covered by a tin roof. Her mother was already in bed. The girl bade her father good night and went to her room. She asked her mother whether she had prayed and then fell asleep. Ahmed stayed up, as is his custom during Ramadan. He was a construction worker in Israel for 10 years and speaks fluent Hebrew.

At about 11 P.M. Ahmed heard the sound of fighter planes in the sky. Residents of the Brazil camp have learned to distinguish between F-16s, drones and Apache helicopters; this time, Ahmed says, it was an F-16. Jet planes in the middle of the night are always bad news, and Ahmed rushed to rouse his daughter and warn her that there might be another night bombing. He told her to open all the windows. This is standard procedure in refugee camps that are used to being bombed – they open the windows in order to reduce the after-effects of the bomb. The boom came a little before midnight, muffled and remote to ears that have already heard everything. Ahmed, certain the nightmare was over, went outside to find out what and who had been bombed. He walked toward the Philadelphi strip and heard from passersby that the target was the home of Sami al-Shaar, the camp’s tunnel baron.

Left at home were the girl, her mother, the second wife and the girl’s aunt. Basama, frightened, asked her daughter to stay by her side in the bedroom. Ahmed went to his brother’s home, which was down the street, not far from al-Shaar’s house, to make sure everything was alright there. At about five minutes past midnight, when he was still in the street, the second bomb struck. Ahmed says he never had heard such an ear-splitting noise. Immediately afterward there was another noise, which Ahmed thought was the whistle of a third bomb, but it was apparently the whoosh of the concrete beam that killed his daughter.

At first the story sounded too fantastic to be credible. True, Ahmed’s brother says he saw the beam flying through the air with his own eyes, and the wires of iron that lie in the small room of Dahm al-Az and Basama confirm his testimony, but the Hamads’ home is about 600 or 700 meters from the bombed house. Can a concrete beam be hurled so far? We asked to see the exact place where it struck, and when we stood on the brink of the huge crater, all doubt vanished. It was definitely possible.

In its response, the IDF Spokesman’s Office noted that the tremendous explosion and the huge crater it left were due in part to explosives hidden in the bombed house: “The IDF attacked from the air a house in Rafah under which a tunnel was dug to transfer arms. After the attack a large explosion occurred at the site, apparently attesting to the presence of large quantities of arms there. According to the IDF’s information, the girl Dahm al-Az was not in the building that was attacked or even in the neighborhood where the attack was carried out, but was in her home and was killed as the result of an accident. The accident apparently has nothing to do with the IDF attack, which, as noted, took place hundreds of meters from the site. Additionally, it is not possible to determine whether the girl’s death occurred at the same time as the IDF attack.”

Shocked, Ahmed hurried home, but his brothers would not let him enter. The sight of Dahm al-Az torn to shreds was too much to bear. Her mother had been saved miraculously by the tin roof, which fell on her and protected her from the concrete beam. The beam shattered when it landed, and only the inner iron wires remained. It left a small crater in the floor and all the tiles had been uprooted, exposing the sand beneath. Drops of the girl’s blood, which was sprayed all over, remain on the wall, even after it was scrubbed.

Her remains were taken to Abu Yusuf al-Najar Hospital. “I went to the hospital and that was it, the end of the story,” the bereaved father says dryly. Her mother, covered by the tin roof, which she could not push off, did not see much. Struggling to tell the story of the horrific experience, she constantly closes one eye and her face reddens, whether because of the effort or the pain. Then she falls silent and cries. When we asked if we could photograph the room where the tragedy occurred, she said no at first. She has not been there since that night. When she finally agreed and was carried to the room, she looked around wildly, her features the embodiment of suffering.

We then trudged through the sand toward the bombed house. It’s a long walk. We walked parallel to the Philadelphi route, on our left, and passed by The Rachel Corrie Kindergarten, named for the American volunteer who was killed here by an IDF bulldozer – it buried her alive. The basketball court next to the kindergarten was shelled a year ago by Israeli tanks, and also lies in ruins. “If I hadn’t seen the beam flying through the air, I would not have believed it,” Dahm al-Az’s uncle says on the way. The children of the Brazil camp followed us with their gaze as we made our way across the sand streets.

The crater that now exists where al-Shaar’s house once stood is astounding. The journalist Azmi Kishawi, who represents France’s Channel One and has covered the Gaza Strip for 19 years, says he has never seen such a huge crater caused by a bomb. We estimate the pit is about 30 to 40 meters across and seven meters deep. Nothing remains of the house other than a few concrete beams lying in the sand, like the one that apparently flew into Dahm al-Az’s bedroom. Maybe the house, which is about 100 meters from the Philadelphi route, had a tunnel under it. A group of youngsters gather around us and stand in a semicircle at the edge of the monster pit. One of them is wearing a t-shirt with the inscription “I hate Israel.”

Angel standing by

All through the night

I’ll be watching over you

All through the night

I’ll be standing over you

And through the bad dreams

I’ll be right there,

Holding your hand

telling you everything is all right

And when you cry

I’ll be right there

Telling you

you were never anything less than beautiful

Oh Lord,

tell me why ?

Why a has Dahm al-Az to die?

She was just 14 years old.

It is terrible. All our discussions on this weblog about former massacres etc. could not safe the life of Dahm al-Az.

As I read the article of Gideon Levy I thougt about the pictures of Roman Vishniac. Roman Vishniac photographed with a hidden camera in the nineteenthirties the life in the Jewish ghetto’s in Eastern-Europe. He did this, because he foresaw that this world would fanish. One picture shows a girl laying in her bed. On the wall behind her flowers are painted. Roman Vishniac: “Since the basemant had no heat, Sara had to stay in bed all winter. Her father painted the flowers for her, the only flowers of her childhood. Warsaw, 1939”

You have my sympathy,