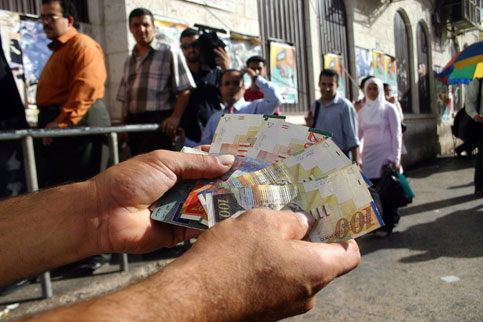

(Gaza en de Westoever hebben geen eigen centrale bank, geen eigen geld, en zijn afhankelijk van de Israelische shekel)

(Fadi Arouri/MaanImages)

Te gast: Ran HaCohen, al vaker aanwezig op dit weblog. Hier, hier en hier.

Keep Israel out of elite economic club

Ran HaCohen, The Electronic Intifada, 17 June 2008

Israel’s ruling elite now has a major aspiration: to join the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as a member country. For the sake of the Israelis and of their neighbors, this aspiration should be thwarted by an international campaign of all supporters of peace; and, in fact, by supporters of the free market as well.

The Paris-based OECD, according to its own website, “brings together the governments of countries committed to democracy and the market economy from around the world.” Established in 1961, the OECD has 30 member countries, including most European states, the US, Canada and Japan, but not Russia, Brazil or India — at least not yet. With a huge budget of 342 million Euro it is one of the most prestigious clubs of nations. Indeed, membership is predominantly a matter of prestige, since unlike the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund, the OECD does not dispense grants or make loans. But prestige means investors’ trust, and investors’ trust means money. Big money.

Israel’s economic elite is intent on achieving the international recognition and prestige that accompanies OECD membership. As demonstrated by the Israeli Ministry of Finance’s special website to promote their membership to the OECD, with details on dozens of working groups, committees, boards and centers, all participating in the national effort to achieve the desired membership. Among other things, the government website claims that “Israel shares the same attachment to the basic values of open market economy and democratic pluralism,” as expected from an OECD member country.

Israel’s commitment to democracy is, of course, fairly limited. The deficiencies are well-known — ranging from lack of separation between State and Religion (banning inter-confessional marriage, for example) to the extensive use of “administrative detention,” i.e. jailing persons for months and years without any charge or trial. On the other hand, several other countries with a highly dubious human rights record, like the US and Turkey, are already OECD members; so the organization itself seems not to take its stated commitment to democracy all too seriously. Focusing on democracy and human rights issues in this context — important as they are — might be playing the wrong card.

A better question for the OECD should be whether Israel can be classified as a free market economy. The answer is: clearly not. If the OECD takes Israel in as a member country, it would prove its commitment to free market economy to be nothing but a joke.

The misconception is anchored in an optical fallacy that seeks to separate “smaller Israel” from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. If we could imagine “smaller Israel” as an economic unit, one could perhaps claim it was a free economy. However, there is no “smaller Israel,” just as there is no economic unit called “smaller Israel.”

With Israel at 60, the memories of its first 19 years as “smaller Israel” (1948-1967) are a remote past, fading even in the minds of the small group of elderly Israelis who grew up in it. The overwhelming majority of Israelis, and Palestinians for this matter too, never knew an occupation-free Israel. It is impossible, both practically and theoretically, to consider Israel without the occupied territories, simply because there is no such Israel. And this is not just a political, psychological or historical fact: it is a clear, tangible economic fact. The economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territories is part and parcel of the Israeli economy. An attempt to view Israel’s economy separately from that of the occupied territories is futile and unserious, not to say ludicrous.

This was an obvious statement 20 years ago, during Israel’s direct occupation of the territories. At that time, the Palestinian market was swallowed by the Israeli economy. Palestinians worked in Israel, paid taxes in Israel, and the entire economy of the West Bank and Gaza were (mis)governed by Israel — through the army and various other Israeli organs.

The establishment of a “Palestinian Authority” (PA) by the Oslo Agreements in the 1990s has created an illusion as if the Palestinians practically have “their own state,” or at least run “their own economy.” Indeed, Palestinians now pay taxes to the PA, which has its own budget, etc. However, this alleged independence — especially in an economic sense — is all but an illusion, as any observer, let alone any serious expert, would be compelled to admit. In fact, Palestinians cannot move a single sack of rice from one place to another without permission from Israel, the “free economy” champion.

The Palestinian territories have no central bank, nor their own currency or monetary sovereignty: they are dependent on the Israeli shekel. Nor do they have declared and internationally recognized borders nor geographic contiguity, a precondition for defining an economic unit. The Palestinian-controlled enclaves are encircled, divided and separated by Israeli roadblocks and by Israeli-controlled areas, like roads closed to Palestinian traffic, Israeli settlements, army facilities etc. Only Israel can decide whether a Palestinian laborer, businessman or entrepreneur may move from one point to another — within his allegedly independent economic unit. The same holds for goods of any kind. Moving a sack of rice from “Palestinian” Hebron to “Palestinian” Bethlehem, both cities located in the West Bank, is dependent on Israeli permissions — for the owner, for the driver, for the truck and for the product. If this goes together with a “commitment to free economy,” then Zimbabwe and North Korea can join OECD just as much.

Israel governs the Palestinian economy not only from within, but also from without. The “Palestinian economy” — in fact a small (five percent) sub-sector of the Israeli economy — is physically and economically encircled by Israel. According to the 1994 Paris Protocol, Israel has a say on the import of any goods into the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Israel alone decides what can be moved (be it wheat, oil, or advanced medical equipment), as well as how much of it, and where from. Given its control on all access gates to the territories (sea, land and air), Israel can physically stop any import; the Palestinians have no effective economic control whatsoever. All this holds for Palestinian export as well. In addition, Israel also sets the taxation (customs, etc.) on goods imported by the Palestinians, so that even the Palestinians’ fiscal policy is in Israel’s hands. Israel is also the one who effectively levies those customs on Palestinian imports, officially “on behalf of the Palestinians.” This means that the tax money goes to the PA — that is, if and when Israel chooses to keep its obligation to transfer it.

Last week, for example, Israel delayed the monthly transfer of Palestinian tax money (some $75 million) — this time as a “punishment” for the appointed PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s letter to the OECD, requesting it not to accept Israel as a member. Even this measure alone, which caused tens of thousands of Palestinian employees not to get their wages on time, should be enough to disqualify Israel from an OECD-membership. At any rate, it is an excellent demonstration of Israel’s deep-rooted contempt to free economy (based on keeping signed agreements) and to democratic values (especially freedom of expression).

All this has far-reaching implications for Israel’s supposedly “free” and “open” economy. In complete contradiction to the very basics of free economy, Israel holds the Palestinians as a captive market. Since the Palestinians cannot import freely, Israel forces them to buy Israeli goods. From fruit and vegetables to plumbing equipment and cement, the Palestinians serve as a dumping market for Israeli goods (often second-class), thus ensuring that Israeli producers have captive consumers, just like in the days of 19th century colonialism. Israel’s economy would have looked totally different if an Israeli dairy giant, or any other Israeli business, did not have seven million Israeli customers, as well as a captive market of 3.5 million Palestinians.

The OECD would therefore make a mockery of its own principles if it allows Israel to join. However, the real issue is not the OECD, but the people of Israel/Palestine. If Israel is allowed to join the OECD, it would be a precious reward for the very elite that runs the political, military and economic occupation of the Palestinian territories: their 19th century-stile colonialist practices would get the stamp of 21st century “free market economy.” If, on the other hand, the OECD turns Israel down, it would be a clear signal that occupation and colonialism cannot go hand-in-hand with free market and with international prestige; and that if Israel wants to join the prestigious club of nations, it should end the occupation first. Therefore everyone committed to peace in the Middle East — from law experts and economists to private citizens and non-governmental organizations — should put pressure on the OECD to keep Israel out until it ends the occupation.

Dr. Ran HaCohen was born in the Netherlands in 1964 and grew up in Israel. He has a BA in Computer Science, an MA in Comparative Literature, and his PhD is in Jewish Studies. He is a university teacher in Israel. He also works as a literary translator (from German, English and Dutch).